Page

Out

Records

Kerry

Links

|

||||

|

|

||||

| Home Page |

Starting Out |

Online Records |

Research Kerry |

Resource Links |

By Pierce Mahony

M.P. for North Meath

London: The Irish Press Agency, 25 Parliament Street.

1887

GLENBEIGH, a name, alas! Now but too well known, is situated on the shores of Dingle Bay, in the south west of the County Kerry. The nearest town is Killorglin, about ten miles distant. The main road from Killorglin to Cahirciveen runs through the property. With the exception of a small quantity of flat land lying between the public road and the seashore, which would be of fair quality if thoroughly drained, the property consists of mountain land of the poorest description. There is as a rule no soil capable of growing crops of any description, except where it has been created at the cost of enormous labour by the inhabitants. The little fields are divided by fences, or rather rude walls made up of huge stones, which the people have collected off the fields in their endeavours to clear the land. Many of these fences are remarkable structures, being several feet in breadth. In addition to these fences, may be seen scattered pretty thickly over the little fields huge piles of stones, lasting monuments to testify to the industry of the inhabitants. With the exception of a few slated houses near the seashore, the houses have all been erected by the tenants, without any assistance from the landlord. Some of them are of the most wretched description; others are substantial of their kind, and not without a certain amount of rude comfort inside.

The extent of the property is a little over 14,000 acres. The rental of the tenanted portion is, as far as I can ascertain, 1,731 pounds, the government valuation about 1,100 pounds. The poor-rate, of which there is one levy in the year, is generally about 4s, 2d, in the pound, and the county cess, of which there are two levies, about 2s, 8d. in the pound each levy - making 5s, 1d. annually. The county cess is paid entirely by the tenants; the poor-rate is divided between the landlord and tenant, though the tenant has to pay it in the first instance. In cases where the valuation of the holding is below one pound, the whole poor-rate is payable by the landlord, the object being that persons liable to become paupers should not be called upon to pay poor-rate. This salutary provision of the law is practically evaded in many cases in Glenbeigh, as I shall point out later on.

Judicial rents were fixed in a number of cases in 1883 and 1884. I have not been able to obtain particulars of all these cases; but in twelve cases which I came across in the course of my enquiries, and which were in no way selected, the average reduction amounted to 27½ per cent. This reduction was given, be it remembered, in the comparatively good years of 1883 and 1884, before the great fall in the price of stock.

Owing to their poverty the majority of the tenants were unable to avail themselves of the benefits of the Land Act. The same cause also deprived them of the benefits of the Arrears Act.

The late owner of the property, Lady Headley, appears to have had the interest of these poor people at heart - at any rate she gave a great deal of employment, which enabled them to pay their rents (at that time very much smaller than they are now). About twenty years ago, the present owner succeeded to the property, and since that time the rents have been more than once raised; the exact amount of the total rise I am unable to give. These rents were never made out of the produce of the land. Still, however, they were regularly paid by the earnings of men who went as labourers, and girls who went as servants, to North Kerry, Limerick, and other places. With the bad times this source of income gradually disappeared; there was no demand for their labour; and consequently their ability to pay rent was reduced to a minimum. Not withstanding this, however, had proper consideration been shown for their condition, and had the former exorbitant rents been largely reduced, they would, I believe, have struggled to pay all they could. Instead of this a series of disputes between the owner and the mortgagees commenced, and agents were constantly changed, there being no less than five in seven years. The tenants, frequently not knowing who had a legal right to the rents, kept the money in their own possession, and soon got heavily into arrear. Being, as a body, men who were always in more or less distressed circumstances, although they might have paid something small if asked for it regularly, when allowed to get into arrear, they naturally used the money to meet other pressing demands.

I shall not further pursue this point, because it appears to be admitted on all sides: - (1) That the tenants got into arrear owing to disputes between the mortgagee and owner; (2) That it is perfectly useless to attempt to recover those arrears.

The main accusation brought against them now is that they made promises which they subsequently broke. In order to understand their present position it is necessary to realize to what extent their ability to pay rent has been affected by the present depression. The labour market failed them in 1879; but even in 1882 the price of mountain stock, their remaining hope, was fairly good. Two and a-half year old heifers, which sold in the autumn of 1882 for six pounds to seven pounds, were sold freely last autumn for from two pounds, ten shillings, to three pounds. Two and a half year old bullocks last autumn fetched from 30s, to two pounds. The fall in the price of mountain stock has been far greater than the fall in other classes, and last year it reached fully 60 per cent, as compared with 1882.

Having said thus much about the change in the prospects of these poor people, I will deal with the accusation that they have broken faith. In August, 1886, Mr. Meyrick Head, the mortgagee, served a notice on the tenants, informing them that an injunction had been issued from the Court of Chancery to restrain Mr. Winn from interfering further in the management of the property, and calling upon them to pay their rents to Messrs. Darley and Roe, Mr. Head's agents. This was followed by the issue of seventy ejectment processes for the October sessions in Killarney. The majority of the men served with these processes, knowing they were utterly unable to pay, and expecting to be decreed in the ordinary way, did not put in an appearance. But since the previous sessions the government had removed the former County Court Judge, and had sent down Judge Curran in his place, for the special purpose of bullying and coercing both the landlords and tenants of Kerry.

The Irish Party proposed last session that the Land Commission should decide between the landlords and tenants of Ireland in a constitutional manner; but the government preferred that this delicate operation should be performed in an unconstitutional manner by a county court judge, utterly ignorant of the nature of the work, and with little or no opportunity of judging of the merits of the cases before him.

Twelve out of the seventy tenants thus served with processes put in an appearance, believing they could defeat the processes on a legal point. When that point was overruled, they expected to be decreed in the ordinary manner; but Judge Curran had previously been in consultation with the agent, and proceeded to ask them could they pay a year's rent and costs, on condition of getting a receipt in full to November, 1885. The first two or three questioned, declared their inability to do so; whereupon Judge Curran immediately informed them that if they did not agree to that, he would decree them for the full amount. To use their own words, they then chose the lesser evil and submitted. This submission to terms it was not in their power to refuse has been represented as a solemn compact and agreement on their part. They were terms which it was utterly out of their power to comply with, and had they even been able to fulfil them, they would still have been left with the millstone of a year's rent around their necks.

In the following November a meeting was held at Glenbeigh; the parish priest took the chair, and in addressing the people commented severely on Judge Curran's action, and testified to the inability of the tenants to fulfil the terms imposed on them. He declared most solemnly his belief that out of the seventy processed not seven could pay a year's rent and costs. Other speakers followed, and the pith of their advice was that the tenants should pay what they fairly could to the landlord; but that they should not strip their farms and deprive themselves of the means of living, in order to effect a temporary settlement.

Mr. Roe, the agent, appeared next day on the scene; and Mr. Roe departed I believe without having received much satisfaction.

Later on a correspondence took place between the Parish Priest and some other persons whose names it is not necessary to mention. The result of this was that, the Parish Priest asked the seventy men under sentence of eviction to meet him in the chapel, and when there he addressed them, urging them in very strong language to consent to pay one gale's rent and costs. He refused to listen to any refusal on their part to do so. He then asked the men who had appeared before Judge Curran to accompany him to Killarney the following day, to see General Buller. This they did, accompanied apparently by five others. General Buller asked them if they would pay a half-year's rent and costs; they promised to do so, and General Buller said he would do all he could to have those terms accepted by the agent.

These men distinctly say that they spoke for themselves, and not for the other tenants from whom they had no authority whatever. It is admitted, however, that the Parish Priest professed to speak for the remainder of the seventy, from whom he had wrung an unwilling consent, or rather silence the day before.

Out of the seventeen men who went to Killarney and promised to pay a gale's rent and costs, fifteen have faithfully fulfilled their promise, and the other two have failed through sheer inability. As an example of the efforts some of these poor men made to fulfil their promise, I may mention the case of two brothers who have sold their oat crop of next year, not yet sown, to a local gentleman. This I ascertain from the gentleman in question to be perfectly true. Of the remainder for whom the Parish Priest undertook to promise, about twenty, as well as I can ascertain, have paid, and some others would have done so, only that they were prevented by the system of joint tenancies, to which I shall presently allude. The Parish Priest admits that he put great pressure on them, in order to extract a promise; and further states that he now knows that many of those he promised for are unable to pay.

It has been alleged that the Parish Priest, Father Quilter, is so disgusted with the conduct of these poor people, that he has refused to have anything further to say to them. Father Quilter utterly denies the truth of this statement; he stated to me that he declined to attempt any further negotiations, because many of the people were so poor as to be unable to offer any terms at present. So far from having abandoned his people in disgust he is full of sympathy for them, is at present acting on the committee for their relief, and has written as follows to the editor of The Pall Mall Gazette: -

"Dear Sir, - Thanks for your letter. I shall be glad to receive any monies which you may have for the people of Glenbeigh, who are being rendered homeless, and will distribute it in the most beneficial way that is within my ability. I am now convinced that some of the people who promised me to pay a gale's rent and costs, which were demanded, did so under the pressure I put upon them to effect a settlement, and that these are now really unable to fulfil that promise.

"I am, yours truly,

"Thomas Quilter, P.P."

I have alluded to joint tenancies. These are in reality groups of tenancies. Each man has his separate portion of land and separate house, and knows his own share of the rent, but the rents of all are joined in one receipt, and their land is valued under one valuation. The effect of this is that if one of the tenants fails to pay his rent, all suffer and are liable to be evicted. Further - if the joint valuation is over one pound, the tenants have to pay poor-rate, and thus in many instances persons who have actually received outdoor relief have been called upon to pay poor-rate.

I could give many examples of these joint tenancies, but one will suffice. A joint tenancy in Reenanallagane is held by some families of the name of Murphy. There are four separate holdings, the total valuation is one pound ten shillings; so they are all liable for poor-rate. Three out of the four families have received outdoor relief in recent years.

In relation to the general poverty of the district, I may mention that the Cahirciveen Board of Guardians has refused to grant outdoor relief, as this division is about 1,100 pounds in debt. Out of this 1,100 pounds, about 700 pounds is due from the landlord. The Cahirciveen Union itself is practically insolvent, and the treasurer has refused to cash its cheques. Last year, Colonel Spaight, the Local Government Inspector, being a humane man, provided several families with seed potatoes out of his private means, and his wife, Mrs. Spaight, collected money for their relief.

It has been freely stated that the people of Glenbeigh have not only refused to pay rent, but also rates and taxes. Regarding the county cess I cannot speak accurately; but I am informed it has lately been fairly well paid.

The last levy of poor-rate was 377 pounds. Of this the landlord is liable for 140 pounds, and the tenants for the remainder 237 pounds. Since the last rate was struck, the tenants have paid 170 pounds - the landlord nothing.

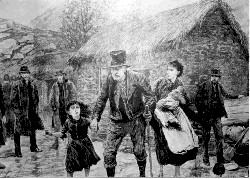

It is not my intention to attempt to describe the inhuman deeds perpetrated by Mr. Roe during the last fortnight. They have been accurately described in the daily press, and have, thank God, evoked a burst of indignation, the effect of which will not stop with Glenbeigh. An attempt, however, has been made to palliate Mr. Roe's shameful deeds, by alleging that he was driven to this course of action by the refusal to pay on the part of men who had the money, and that he has been forbearing and even generous to those who were unable to pay.

There was a tenant named Thomas Bourke who had a wife and four children. For years these people were well known to have lived on the charity of their neighbours, and the wife appeared to be afflicted mentally. They were frequently in receipt of outdoor relief. The whole family were a picture of poverty; they had no stock. Their rent was five pounds; their valuation only three pounds four shillings. The appearance of the ill-clad, shivering children would have melted the heart of most men; but Mr. Roe was unaffected. He demanded his rent and costs. Bourke was utterly unable to comply with the demand - so he, his wife and his children, were flung out on a severe winter day, and their little house burnt before their eyes. The Constabulary who had to perform the loathsome work of protecting Mr. Roe and his gang were so moved at the sight, that they made up a subscription on the spot for the unfortunate family. Bourke and his family being absolutely destitute, have received provisional relief from the relieving officer, acting under the instructions of Colonel Spaight, from whom special instructions were necessary, as the Cahirciveen Union is at present practically insolvent.

The only other case to which I shall call special attention is that of the brothers Thomas and Patrick Diggins. Thomas Diggins has a wife and eight children, the youngest only three weeks old. Patrick has a wife and six children. They lived in separate but adjoining houses which they and their father had built, and to which the landlord contributed nothing. They occupied separate holdings, but were joined in one tenancy and one receipt. Their joint valuation being five pounds 15 shillings, they were liable for poor-rate. Neither of these men was in a position to pay on the terms offered. Thomas had no stock or other means. Patrick had two little cows. Terrified at the idea of being deprived of his home, Patrick sold one of his cows, and his daughter, who is in service in Limerick, sent him a little help. In this way he was able, when the Sheriff and the evicting party appeared, to offer to Mr. Roe the amount demanded including costs. Mr. Roe, however, would not accept it unless his brother paid for his house and his land. The Sheriff implored Mr. Roe to take the money from Patrick, and deal with the two cases separately. This Mr. Roe declined to do; and, owing to the system of joint tenancies in vogue on this property, he was within his legal right. Thomas being destitute was unable to make any offer, beyond a promise that he would do his best if Mr. Roe gave him two months time. But this was not Mr. Roe's mission to Glenbeigh; so in spite of the entreaties of the Sheriff, and the tears of the unfortunate peasants, he burnt both houses, levelled them to the ground, and by this one inhuman act rendered homeless eighteen souls in the midst of a severe and terrible winter.

In spite of the horrible atrocity of these deeds, Mr. Roe, I am informed, has frequently stated that he has been acting throughout under the advice of a government official in high quarters. One thing is perfectly clear, and that is that the government have protected Mr. Roe in his inhuman work. The Sheriff, as I understand, in the first instance asked for sixty police to protect him in the execution of his duties. When Mr. Roe began to burn the houses, the Sheriff, or rather his deputy who was acting for him, retired with his men, and called on the police to follow him. This they did not do, but remained to protect Mr. Roe. Since then a further force of police has been drafted to Glenbeigh to protect Mr. Roe. The Sheriff's duty ends when he hands over formal possession to the landlord's agent, and the Sheriff at Glenbeigh made this quite clear by retiring to a distance with his bailiffs as soon as he had handed over possession. The police, however, acting under orders, remained to protect Mr. Roe in his work of burning and demolishing the houses. I protested against the police being employed for such work as this, and was told it was their duty to remain to prevent a breach of the peace.

If for the purpose of expediting matters, Mr. Roe had merely taken formal possession of a number of houses, and returned on a future day without the Sheriff to carry out his legal right of burning and levelling these houses, would the government have dared to afford him police protection? I think not. It is one thing to prevent a breach of the peace. It is another to protect a man in conduct which incites others to commit a breach of the peace; and yet I maintain this is precisely what the government have been doing.

The members of Parliament present, of whom two were English members, addressed a telegram to the Chief Secretary. The telegram speaks for itself; and so does the answer. Mr. Fry had left before the answer came, and so could not join in the reply to it, or rather the comment on it; for after such a reply, based as it clearly was on the representation of one side only, it was useless to communicate further with a partisan Chief Secretary. The following is a copy of the telegram sent to Sir Michael Hicks Beach, and of his reply: -

"We appeal to you personally to come to Glenbeigh, and see for yourself what the government is permitting. Not only are the police being used to protect the Sheriff in the execution of his duty, but after he has given over possession and retired with his bailiffs, the police are further used to protect Roe, the agent, and his men in their work of levelling and burning the tenants' houses. The weather is fearful, and the work is simply inhuman.

"Signed, "C.A.V. Conybeare, Theodore Fry, Edward Harrington, Pierce Mahony, Jeremiah D. Sheehan."

To this the Chief Secretary replied: -

"Messrs. Conybeare, Sheehan, Fry, Mahony, and Harrington, Glenbeigh, - It is not possible for me to go to Glenbeigh, and from all the accounts it appears that the police are only protecting the owners in the necessary enforcement of their rights. Any sufferings, though much to be regretted, are already due to others.

"Hicks-Beach, Downing-street, London."

On this reply we commented as follows: -

"In reference to the telegram, we are quite prepared to leave it to the judgment of the public, and have only this observation to make: Sir Michael Hicks-Beach having thought fit to state that the suffering inflicted on this tenantry is due to others, it seems to us that he is clearly bound to explain this statement, and to make public his proofs, or the authority on which he has made it. We, who are on the spot, and have made most assiduous enquiries, utterly deny that there is a shadow of foundation for such a statement.

"C. A. V. Conybeare, John Dillon, Edward Harrington, Pierce Mahony,"

On the evening of Friday, 21st January, Mr. Roe expressed an anxiety to come to terms, and we received the following communication from him: -

"I will agree to accept a half year's rent and costs already incurred, from each tenant on the estate, and will give receipt in full up to 1st May, 1886. I will undertake to sign a consent to enable the Land Commissioners' Court to fix each tenant's rent as if he were a present tenant. I shall make a special application to the Land Commission, and have their cases heard at the earliest possible date, providing that all that are willing to take advantage of the Land Act of 1881, serve originating notices upon me within ten days from this date. This offer will remain open until eleven o'clock, a.m. tomorrow, 21st January, 1887."

To this we replied: -

"That we, being desirous to aid in bringing about a settlement of these cases, are willing to act as the representatives of the tenants. With this view we have lost no time in collecting information as to their condition and their views; and we now propose at 12:30 tomorrow, Friday, to lay before Mr. Roe such proposals as, after consultation with them, we may be prepared to offer in their behalf.

"John Dillon, Pierce Mahony, C. A. V. Conybeare, Edward Harrington."

The next document from the agent was: -

"Being desirous to effect an amicable settlement with the tenants on above estate, I am willing to stay further proceedings until 12:30 p.m. tomorrow, 21st January, in order to afford them a further opportunity of accepting the terms which I have offered them in my previous memorandum of this day's date."

To this the following reply was sent: -

"From Mr. Roe's answer, it appears perfectly clear to us that he has no real desire for a settlement, as he has merely repeated his offer of November last. Under these circumstances, there is no course open to us but to do all in our power to protect the tenants against the barbarous and inhuman action of Mr. Roe.

"John Dillon, Pierce Mahony, Edward Harrington, C. A. V. Conybeare,"

The tenants had already given the most remarkable proof of their inability to accept Mr. Roe's terms, by permitting their houses to be burned and levelled to the ground; it was therefore useless for us to press the matter further.

It has been stated that the present state of affairs in Glenbeigh is entirely due to the action of the National League. The meeting in November last was called for the purpose of protesting against Judge Curran's action in Killarney, and declaring the inability of the tenants to fulfil Judge Curran's terms: General Buller by his action has testified his belief in this inability. Since that meeting, and the subsequent alteration of terms under General Buller's pressure, the National League has not interfered. Had the League done so, Mr. Dillon, as he himself said at Killorglin on 27th January, would have been the first man in Ireland to know of it. And yet we have his statement that until these evictions commenced he did not even know the name of the property. The fact is, no combination against payment of rent existed in Glenbeigh; what did exist, and still exists, is inability to pay. The strongest proof that there is no combination against payment, is the fact that about one-third of the tenants have paid, and that there is not the slightest ill-feeling against them for having done so.

As a proof that the National League has not prevented them from paying, I may mention that the committee of the local branch of the National League has amongst its members fourteen tenants from this estate. Out of that fourteen, eight have paid. At the end of Mr. Roe's letter to The Times, the following paragraph appears: -

"The tenants could without difficulty have paid the amount asked - one half year's rent out of five in most cases, and it is an extraordinary fact that until the appearance of Mr. Harrington on the scene they were willing to do so, and some actually did settle."

Regarding this it is only necessary to remark, that from the time General Buller's offer was made, Mr. Harrington was not in the neighbourhood until the evictions were in full swing - in fact he did not arrive until after five houses had been burnt and levelled, and the unfortunate people had given this striking testimony of their inability to comply with Mr. Roe's terms. This scarcely tallies with Mr. Roe's statement, that the tenants were willing to pay until Mr. Harrington appeared.

The terms offered have frequently been described as a demand for only half a year's rent - it should be half a year's rent and costs. The importance of this will be manifest from the following example. The rent of Cornelius Griffin is two pounds a year. The half year's rent demanded was therefore one pound, but the costs amounted to two pounds 15s, 10d. - so that Griffin was asked to pay, not half a year's rent, but a sum equal to two year's rent, less 4s. 2d.

One of the most sickening sights of all this sickening tragedy was the cold barbarity with which Mr. Roe witnessed these distressing scenes - nothing seemed to touch his stony heart. The wife of Maurice Quirke had been an invalid for years. The Sheriff faltered at the idea of removing her; but the dispensary doctor was ready at hand, and gave a certificate that she was fit for removal, so Mr. Roe insisted that the eviction should be completed. Thus on a wet and cold winter's day, this poor woman, with the mark of death already graven plainly on her brow, was led out, and she had scarcely crossed the threshold when the crowbars were clanging in the horrible work of destruction. It was indeed a sight to make one exclaim, Is this really a Christian land?

This brutal work still goes on, but the force of public opinion has mitigated the brutality. A heavy blow has been dealt to these unfortunate people; but a heavier still to the system under which such barbarities are possible.

Thanks to Mary Ann Schloegl for sharing it with us!